The world has a waste problem.

Recycling is part of the solution, but it’s not the whole solution. We can’t recycle our way out of a waste crisis. You can trust us, we’re the ones doing the recycling..

Recycling isn’t a new concept. Perhaps the word “recycle” hasn’t been around for long, first coined in the 1920’s, and only really entering the mainstream lexicon in the 1960s and 70s. The concept itself however, has been around as long as people have been around. “The idea that you threw stuff out when it wore out is a 20th Century idea” and a product of “a consumer culture that suggested that the new was better than the old,” says Susan Strasser, author of Waste and Want: A social history of trash.

Picture: Women sitting on flour sacks which were used to make clothing.

Reuse and repair was an ingrained part of society, before the disposable products of the late 20th century became common-use. The term recycling became a buzzword, not because of the value lost by disposing of our products, but because the increase in waste was becoming a problem. Suddenly recycling became the catch-all fix for the exponentially increasing waste problem, while not changing existing behaviour, systems or habits around consumption.

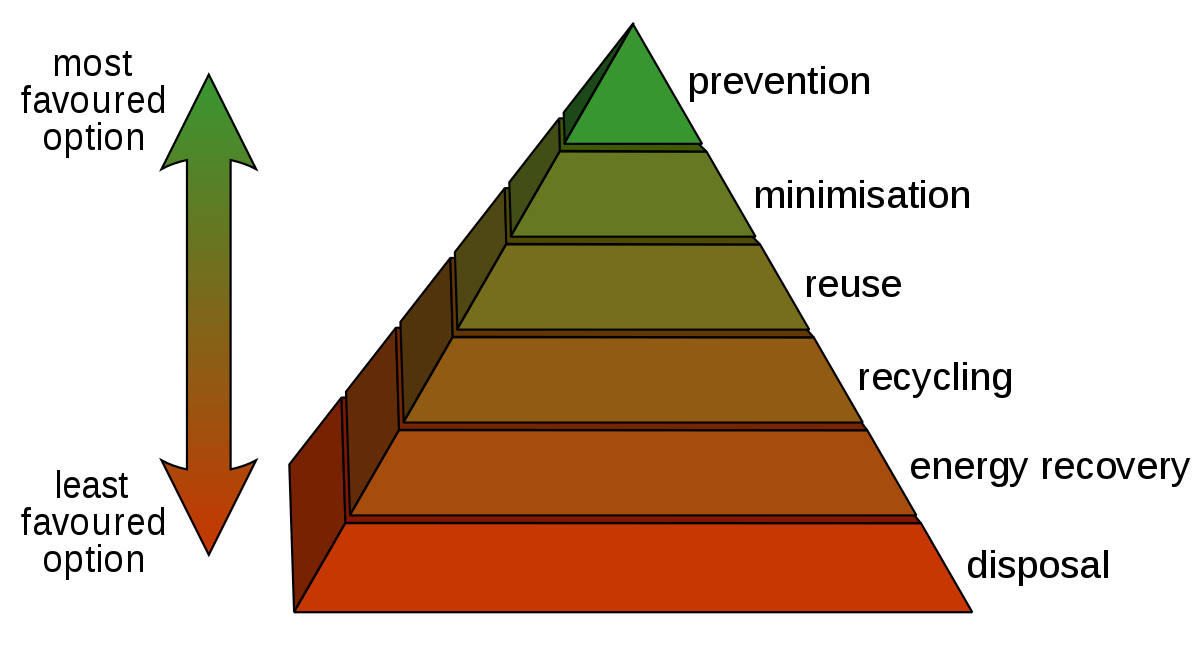

However we know that recycling ISN’T the answer in and of itself. It is one of the parts of a multifaceted response to waste, which sits within the “waste hierarchy”. Recycling is actually lower on the waste hierarchy than you might think.

The waste heirarchy is a tool used in the evaluation of waste management processes that take into account all areas of sustainability, including resource and energy consumption, and inherent value lost.

We don’t think the waste hierarchy is going to come as news to that many people reading this article. We’ve all had “reduce, reuse, recycle” in our heads for years. But there are still plenty of opportunities, risks and unknowns in the emerging circular economy, and greenwashing exercises have made information surrounding our waste crisis more confusing. We shouldn’t forget that our behaviour around waste is essentially our behaviour around consumption, which in turn influences our spending habits.

When we create a product, we imbibe it with a thing known as embodied energy. Embodied energy measures the raw materials, resources, energy consumption and human hours that went into creating that product. Take a mobile phone for example; mobile phones contain rare and precious metals, along with other commodities. Those commodities had to be mined, go through the manufacturing process and then built into that phone you purchased. For each process it used energy that in a world that still uses fossil fuels, had an environmental impact. Your phone comes with so much embodied energy stored inside it before you’ve even taken it out of the box. For a mobile phone, the amount of energy it took to create it means we should be using it for a MINIMUM of twenty five years. Yet no-one would be able to hold on to our smart phone for that long, nor has there been a company making such a product. While a phone has a high concentration of gold, silver, copper, cobalt and more, the moment we recycle it, we lose so much of that embodied energy.

Recycling is necessary, incredibly useful and inevitable. However, improving practices around the other elements of the waste hierarchy in tandem with recycling is key to managing our waste crisis.

Prevention / Reduce

Prevention comes in many forms. The first step is obviously to minimise our consumption. By consuming less, we make less products, we create less waste. Companies tend to greenwash products to make you think your purchase won’t make an impact, but the best way to stop a product having an environmental impact, is to NOT buy it unless you need it. No matter how many sustainability targets they claim to meet. Even if we manage to recycle every item we purchase, energy and precious materials are still lost in the downstream processes. And so preventing and minimising our consumption when we can, is always going to be step number one.

Not to put all of the responsibility onto the consumer. This ‘take-make-waste’ model that we live in was created during a time when human-kind’s impact on the planet was less clear. Manufacturing is changing and some proactive manufacturers are changing their business models to shift away from the take-make-waste model. There is still a long way to go, but the system we live in can move very fast when it needs to.

Repair and re-use

Reducing our consumption also comes down to re-using what we already have, and repairing it when it breaks. Things like repair cafe’s and the right to repair laws are a big step in prevention too.

We will inevitably need to replace items that still work, but have run its use course for us. Electronics is the big one for replacement BEFORE it breaks. With ever changing technology and software, a computer that was top of the line a few years ago is no longer fast enough to run the software we need in our jobs or for our hobbies. We have a growing number of options to give our products a second life, with facebook marketplace, buy nothing pages and gumtree growing exponentially, highlighting how much value we were simply throwing in the bin over the previous decades.

We have welcomed the investigation and hope to see legislated “right to repair” laws which will further strengthen this growing phenomenon, by enabling more repair and reuse of patented products. The right to repair laws don’t only prevent us from having to throw products away, but with new regulations such as the repairability index it will impact how things are made. When the responsibility of repair is put back onto the manufacturers, they will have to create products that are easier to maintain and repair.

When it comes to electronics, repair and re-use is the often overlooked option. At Total Green Recycling we started the asset recovery side of the business when we realised how many working items were coming through our warehouse. You can read more about how this works here: Asset recovery, what is it and why is it important?

Recycle

Eventually all products reach the end of their useful life, whether through obsolescence or through general wear and tear. It’s important to ensure that your product or device is at the end of its life when it goes for material recovery. As outlined above, the embodied value of products must be preserved as much as possible.

Our recycling process isn’t perfect in Australia and products aren’t typically made with recycling or repair in mind. As we don’t have the reprocessing capability onshore and due to use of certain materials in products (think plastics and metals bound together, e.g. fruit juice cartons), recycling usually has a percentage that goes to landfill, until we can find another solution. As new regulations come into place, Australia is investing in new manufacturing and recycling facilities, such as plastic recycling plants to combat the challenge of the export bans. It is technically possible to recycle nearly everything, but Australia just doesn’t have all of the infrastructure yet. Plus we as a nation, don’t understand how to recycle well enough so there are plenty of recyclable materials still ending up in landfill due to contamination. Which is why recycling sits where it sits on the hierarchy.

There are different types of recycling that are higher and lower on the waste hierarchy.

3.1 Open loop and closed loop recycling.

Closed Loop recycling is next on the hierarchy, as a product is completely recycled and turned back into its original product. Structural steel, glass bottles and so on are examples of closed loop recycling. The commodity doesn’t lose value or purity through the process and it can be recycled in perpetuity. Although any form of recycling still requires massive amounts of energy and resources. So until all of our energy is sustainable, there is no completely green form of recycling.

Open loop recycling is a step lower in the hierarchy. For certain recycling processes we can’t retain the original value and purity of the material, and instead it is recycled into a different product. Like using plastic in the road base, or recycling steel from a car. Steel from the transport industry can become contaminated with copper or tin and becomes unusable for those same products. So it is downcycled into the construction industry instead where some contamination is acceptable.

Waste to energy

WtE is the production of energy from biomass materials such as the by-product of food and domestic and industrial waste management systems. There are many different WtE schemes being employed in the world. Incinerating waste to create thermal energy is one major form being used across the world.

Other options are fermentation to create ethanol, esterification which creates biodiesel, pyrolysis converts plastic into fuel, biogas which is created through anaerobic digestion of agricultural and food waste.

Waste to energy is preferred over landfill, but various forms of it still create emissions. Incinerating waste is better than landfilling it, as landfills emit gases that are 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide, however incinerating still creates emissions.

New forms of WtE are being discovered which perhaps will have less of an environmental impact than our past options.

Australia is still lagging in our Waste to Energy schemes, with only 0.9 percent of our energy coming from Waste to Energy schemes. However two large plants are under construction in WA with capacity to take almost all the waste generated.

Waste to energy is the more environmentally friendly and sustainable option of waste management compared to landfill. But this is why we have the hierarchy, because again this should be the final option. Once every other option has been attempted, to retain some small value from the waste by creating energy and minimising waste.

Disposal

In the Circular economy, landfill should not exist. It is a potentially hazardous and unnecessary waste disposal form that is better than simply leaving our rubbish in our house or at our business (Although if we did that, i’m sure we’d very quickly stop producing as much)

Landfilling waste comes with risks such as the potential for fire , dangerous chemicals contaminating soil and ground water, emission of gasses that are far more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. This is in the process of being phased out and although will still be required for years to come, volumes will significantly reduce making our economy more sustainable.

Recycling is an inevitability – improving the recycling outcomes is the key. Government, Industry and the individual are all key stakeholders and working together will make this improve the current state of play. Australia is still lagging behind the rest of the world when it comes to our recycling and waste to energy industries, along with our right to repair laws.

When Total Green Recycling started almost 14 years ago now, there was barely an industry. The directors were collecting computers and televisions from verge side collections. Today, while there is still electronics making their way onto the verge, most of them are being picked up by councils and taken to our facility, rather than ending up in landfill. And in 2024 we won’t be seeing any electronics in landfill, with the ban on e-waste to landfill. Our understanding of recycling and waste disposal has changed dramatically. Our access to better end of life options is increasing. The way we shop, the products we buy, our ability to repair is shifting. We still have a long way to go, but we’re picking up our pace.