The waste export ban is an important step towards the circular economy, but what does it really mean for Australia’s recycling industry?

The Problem

Total Green Recycling and many other environmentally friendly companies are taking steps towards the Circular economy. Unfortunately the world at large is still operating under the unsustainable “take-make-waste” economic model. The waste we generate annually continues to grow, and our valuable virgin resources continue to diminish.

In 2017 China stopped importing certain foreign waste products. Suddenly the waste problem became a waste crisis. With China no longer accepting the world’s waste, it has been diverted to other developing countries, who are increasingly following China’s lead and saying “no” to importing contaminated recyclates. Not to mention the fact that, with 2 billion tonnes of waste generated annually, it would be a massive imposition to expect these developing countries to possess the infrastructure, let alone accept such high volumes of waste in the first place.

A solution?

In 2020 the Australian government passed the Recycling and waste Reduction Act. Unprocessed waste can no longer be exported overseas unchecked. On paper, this means our waste will be processed and refined in Australia, so it can either be used locally or exported in a refined state with regulatory oversight. In practice, it’s not so simple though.

First let’s take a look at how recycling actually works?

The process of recycling, takes particular waste products and puts them through a specific process to extract, wholly or in part, the usable and valuable commodities for further processing. Electronic waste as a recycling stream, contains precious metals, steel, plastic, glass etc. which eventually flow into manufacturing and construction industries.

As Australia’s manufacturing industry has retracted significantly over the years, much of our recycled material will still be exported offshore. However instead of sending unprocessed and contaminated materials that can have negative environmental impacts, we send high quality and regulated materials. It is no different to exporting iron ore, or other virgin commodities.

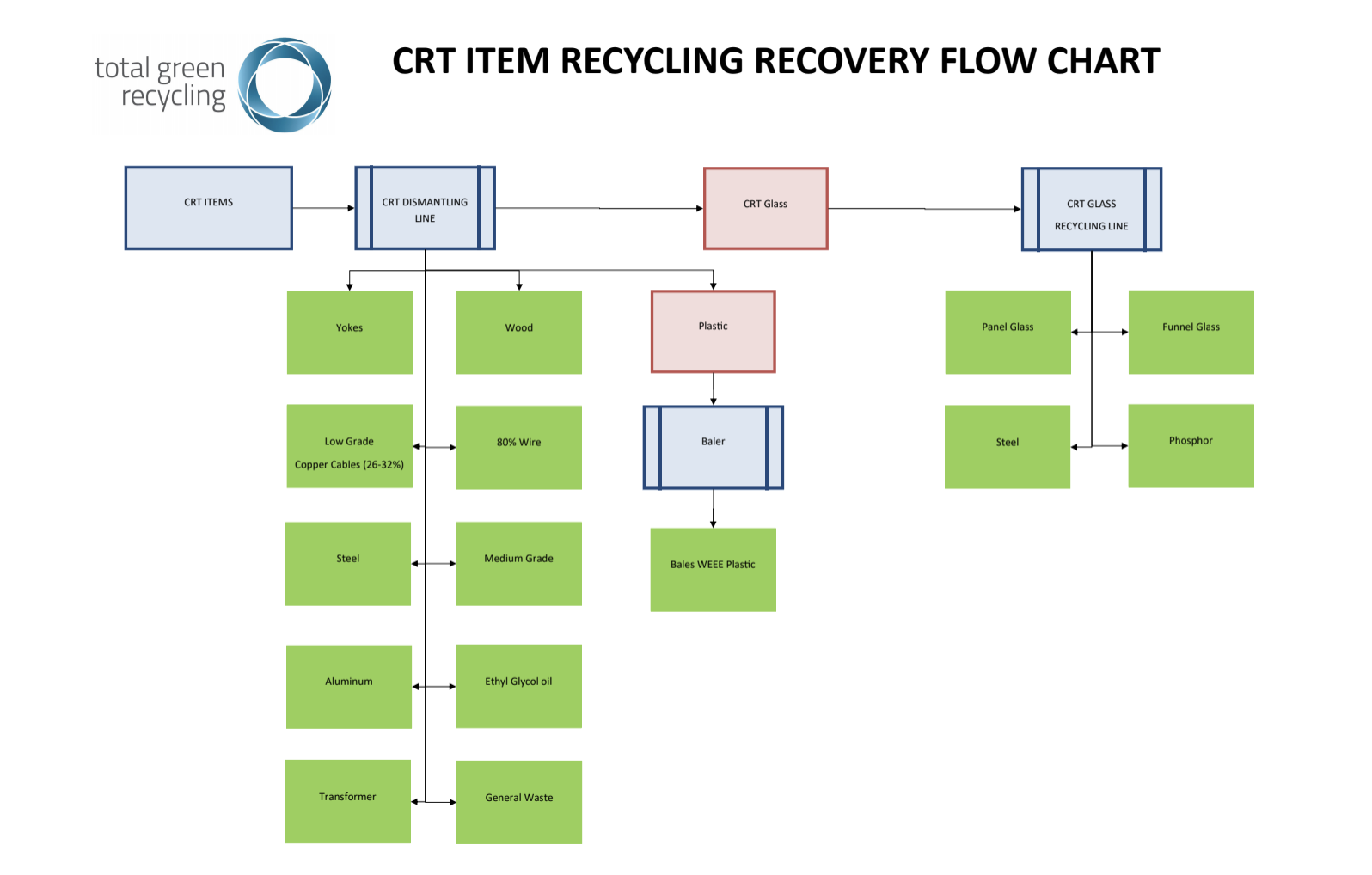

Let’s dive in a little deeper and have a look at a specific recycling flow chart. Our CRT glass recycling process is an ideal example of this process. First Total Green Recycling dismantle these CRT items into their separate materials, as you can see below.

Each item is processed separately, but for now, we’re going to take a deeper look into how our CRT glass is further refined. CRT glass contains a number of different materials, which if not processed correctly are hazardous to health and the environment, the main one being Lead. Total Green Recycling doesn’t have the facilities to extract and refine the lead into ingots, so we have partnered with Nyrstar in Port Pirie in SA which is one of the world’s largest primary lead smelting facilities and the third largest silver producer.

Nyrstar has invested billions in the infrastructure needed to transform the leaded glass into usable materials, which is why we have partnered with them instead of trying to do the process in house. It just wouldn’t make economic sense.

These valuable resources are recovered through a variety of metallurgical processes and returned to the manufacturing industry, displacing virgin materials.

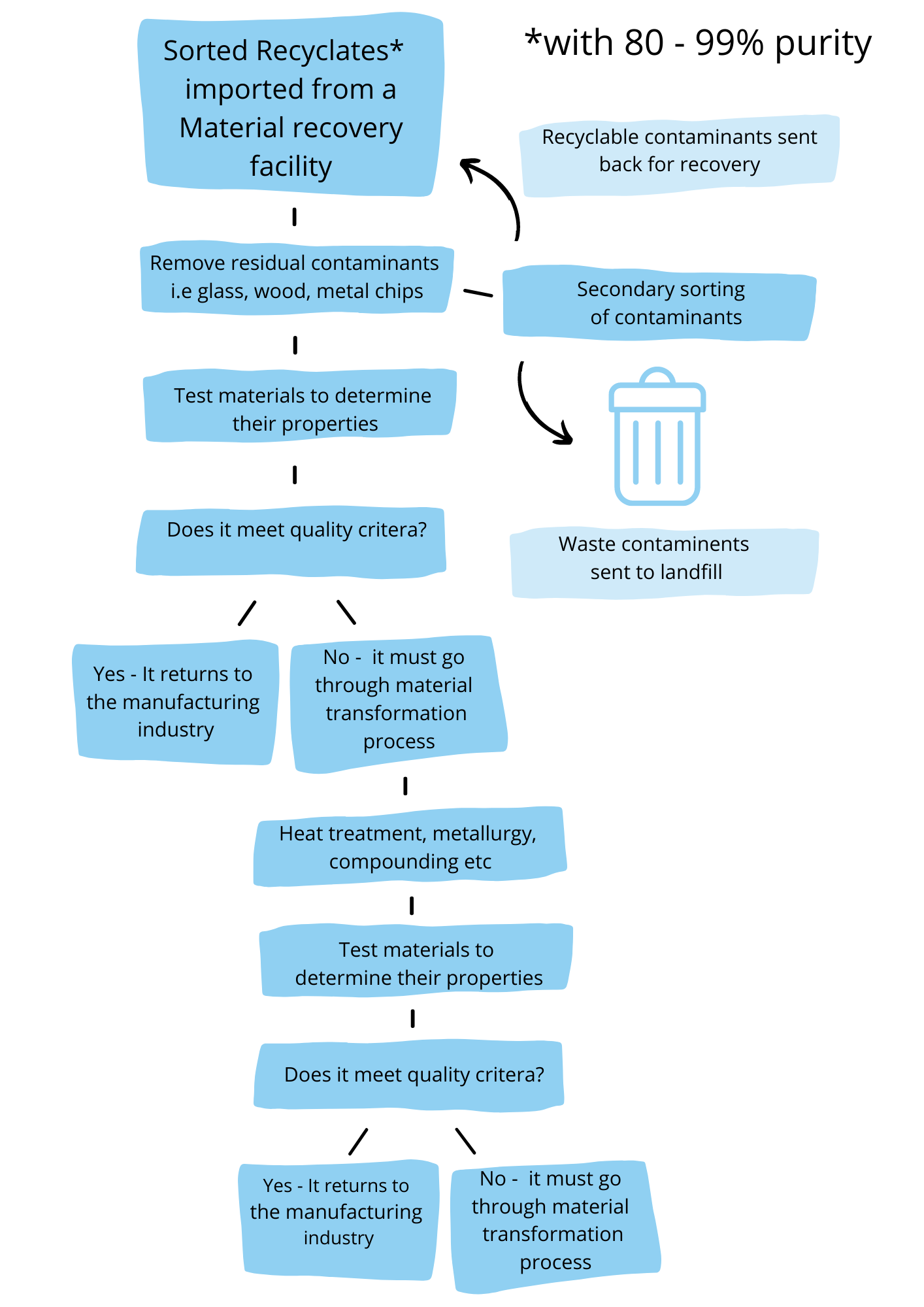

Recycling electronic waste isn’t as simple as taking apart the separate materials and returning them to the manufacturing industry. All materials flow through a process as complex and nuanced as the process for extracting lead from CRT glass. It requires rigorous testing, followed by specialised transformation processes. Such as metallurgy, heat treatment, compounding etc.

What the waste export ban means for these processes?

It is technically possible to recycle 100% of our waste. However, practically, it hasn’t been economically viable to install the infrastructure required to do so. And so Australia does not currently have the ability to refine and use all of the materials contained in the “waste” we are generating.

Port Pirie Lead smelter

We don’t have facilities like the Port Pirie lead smelter for every waste stream. For example, much of the plastic we recover from electronic waste cannot be further processed in Australia as we don’t have local facilities to transform specific plastic into a manufacturing ready material. In the past it has been exported off-shore to be cleaned, refined and compounded so it can be returned to the manufacturing industry. A complete export ban would result in a lot of this material ending up in landfill whilst industry develops. Thankfully, a waste export licence system is being established, to allow legitimate export processes to continue whilst still being controlled through a regulatory process

Big potential for long term benefits

The government understands we have a problem and is willing to work towards a solution. It’s forcing industry to focus on innovative solutions at a local level, which may lead to the development of more local manufacturing in Perth and across Australia.

If proven successful this will lead to better management of our waste streams, and has the potential to boost local economies and provide new green jobs.

We see this as a big step forward on a long pathway towards a circular system with the ability to completely recycle products and divert waste from landfill. However, with complex, multi-layered problems, there is no easy solution, which is why timely and consistent reviews and tweaks to the regulations will be needed to get the best outcomes.

Short term issues

The Waste Export Licence Declaration (WELD) portal has been established, which allows for materials to still be exported, provided they meet specification requirements. Like any new system, there will be challenges and unintended outcomes to be worked through. In the early stages of the new scheme its possible that we will see :

- Temporary landfilling of recyclable material that previously had export markets whilst industry scrambles to install infrastructure to meet the required specification or establish supply chains to meet the WELD requirements

- Stockpiling of recyclables for the reasons mentioned above

- Increased gate fees from recycling companies to pay for the additional capital and operating costs to meet the material requirements for export

- Landfilling of materials that prior to the ban attracted a rebate from the commodity value but are now more costly to process than the commodity value

These are all the issues that will need to be addressed in the early stages of the Ban. Nearly all the issues identified above are influenced by the economic drivers. Incentivising outcomes will be a critical part of the solution.

Long Term Benefits

The Waste Export Ban essentially forces Australians to take responsibility for their waste, not only does this benefit the environment but it also has the potential to benefit us economically. There is potential for this legislation to:

- Drive innovation and further Australia’s technical capabilities in material science and refining

- Create new industries and green jobs.

- Promote better consumption habits leading to a less wasteful society

- Slow down climate change which has huge economic implications for Australia.

The waste ban ALONE will not fix the overwhelming problems we face. To have a long lasting positive impact, it needs to be coupled with investment in infrastructure and innovation, along with regulations and supporting programs like product stewardship schemes.

“The Waste Export ban has exposed the shortcomings in our systems. This is half the battle, knowing where our shortcomings are so we can fix the problems. For too long we have exported our problems, but perhaps now we can see them clearly, we come up with innovating solutions. to address the root cause, being unsustainable consumption,” says James Coghill, director of TGR. “We can’t simply recycle our way out of the problem, we have to think bigger and look at what and how we consume.”